It was an episode of Who Do You Think You Are that made me want to look again at my Ascough family history. Former minister Edd Balls is taken back to the nineteenth century and a radical ancestor, an agricultural labourer who stood up to the changes in farming in Norfolk, especially mechanisation that threatened their livelihoods. Not far away were the Ascoughs, also agricultural labourers.

I wanted to be reminded of what the changes of that same century meant for my ancestors living on the edge of East Fen in Lincolnshire. I had found five generations who lived there from Thomas Ascough (born 1735) to John Ascough (born 1758), his son John Ayscough (born 1781) then James Ascough (born 1808) and finally George Askew (born 1852). More detail is on my post of 26th December 2015 The George Askew Story Part 1 - Five Generations of Agricultural Labourers. However, it was my later post of 15th August 2016 The George Askew Story - Part 2.that explored their lives in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

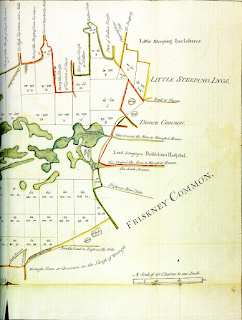

There are no records of the Ascoughs before Thomas. If they were in the same locality, this is what I found. Going way back in time, I noted in my post of 12th November 2017, "The Great Inquest (of the Soke of Bolinbroke 1548) set out to organise how the fen commoners used the common land of the fens to the advantage of all. This included the area of the East Fen and particularly The Deeps that provided such a good living for the commoners. These are described in more detail later. The map below is dated 1661.

However, if we start with the birth of Thomas Ascough in 1735, East Fen is shown in the picture below that is dated 1774 when he was thirty nine. It already shows the first drains that were to eventually eliminate The Deeps a whole century later.

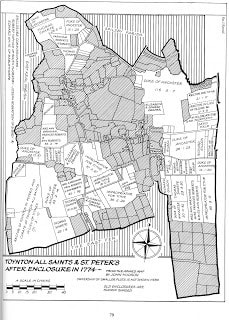

At the same time as the common land of The Deeps was under threat with those drains shown above, and more to come, the enclosure of the common lands around the villages of Toynton St Peter and Toynton All Saints (those open fields shown in the map below) took place through the Enclosure Act of 1774. So both the common land around the villages and the common land of the Fen were about to become extinct. The life of the commoners was to change in the most dramatic way.

This is some of what I included in my website https://theascoughsofeastfen.weebly.com.

THE TOYNTON VILLAGES BEFORE AND AFTER ENCLOSURE

It is evident that the inhabitants of the two villages lived a kind of double life. The East Fen certainly provided one type of livelihood. But it was the fields and common land close to the village centres that allowed the commoners to graze livestock in the winter, and to grow crops on strips that were ploughed for their use. It is clear from both the following surveys that before enclosure in 1774, the majority of the land was common land described as Open Fields.

This combination of farming on common land close to the villages and the benefits they gained from the open East Fen meant that the commoners living in the Toyntons must have enjoyed a reasonable and independent lifestyle for many centuries. This was all to change with the draining and enclosure of East Fen and the enclosure of all the Open Fields around the villages.

The enclosure of the two Toynton Villages is described in two parts. The first is the situation at the beginning of the seventeenth century as detailed in a survey carried out in 1614. This shows that some enclosure had already taken place. The second is the position at 1773 before the Enclosure Act of 1774, and then how the Act enclosed the remaining open fields.

What is interesting is that a comparison between the 1614 survey and that at 1773 showed very little had changed over that time. The question is, were the Ascoughs reliant upon the common land (Open Fields) for their livelihood or were they employed to work for the owners and tenants of the enclosed fields? My guess is probably both.

THE ENCLOSURE OF TOYNTON ALL SAINTS AND TOYNTON ST PETER’S: 1773-1774

There is no sign of any Ascough being allotted land, so may not have enjoyed any rights of common at that time. That might have meant that they had no livestock to graze on the East Fen as these would have had to be moved to the higher Open Fields in winter.

What the Enclosure does show is that the parish did not suffer from flooding as the land is slightly above the level of the East Fen. Indeed, Toynton St Peter is around 10 metres above the Fen and Toynton All Saints at 30 metres according to the latest OS map. The southern boundary of the parish enclosure seems to be where the East Fen Catchwater Drain was placed through the Act of Parliament of 1801 and 1803.

The pools were connected by “Havens”, “Rows” or “Boating’s” and it was a pleasant excursion in the summer to row from pool to pool the entire length to Wainfleet. They also enabled the transport of goods including livestock, to the harbour there.

The centre of each pool was free from weeds and although the bottom was mud, perhaps three feet deep, above was three to four feet of amazingly clear water. It was therefore easy to see and catch fish with a net or even a hay-fork.

For fuel the fenmen used peat, dug in “turf fens” and dried. A week’s work was usually sufficient to provided firing for the whole year. For thatch, they had reeds cut from reed ponds; osiers (species of willow) were also important as were rushes (for flooring, bedding etc).

In the waters and among the reeds, fish and fowl still continued in abundance. Fish included perch and eels, and especially tench and pike. Quite as familiar a fenland figure was the fowler. The older method of catching large numbers of fowl was to drive them wholesale into a net at the end of a pool or mere, with the aid of a large number of assistants and boats. (J Ray and F Willoughby “Ornithology” 1678). There were vast quantities of geese yielding large amounts of quills and feathers as well as meat.

The independent commoners who eked a living from the fens often lived in basic and very poor accommodation. Cottages were not built to last but put together with materials easily and freely available. (Mud and stud walls) the roofs were thatched with reed and turf and the heating would be peat and wood. There was generally no chimney, just a hole in the roof and the smoke went out of the door and any windows. The acrid peat smoke had the benefit of keeping out biting insects, particularly midges and mosquitoes, in the summer.

No comments:

Post a Comment